As many readers know, October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month. What that generally means at our cancer center and in the rest of the “real world” is that, during the month of October, extra effort is made to try to raise awareness of breast cancer, to raise money for research, and promote screening for cancer. Unfortunately, what Breast Cancer Awareness Month means around the Science-Based Medicine blog is that a lot of breast cancer-related pseudoscience and outright quackery will be coming at us fast and furious. There’s no way, of course, that I can deal with it all, but there’s one area of medical pseudoscience related to breast cancer that I just realized that none of us has written about on SBM yet. Actually, it’s not really pseudoscience. At least, the specific technology isn’t. What is pseudoscience is the way it’s applied to breast cancer and in particular the way so many “alternative” medicine and “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) practitioners market this technology to women. The technology is breast thermography, and the claim is that it’s far better than mammography for the early detection of breast cancer, that it detects cancer far earlier.

I’ve actually been meaning to write about thermography, the dubious claims made for it with regard to breast cancer, and the even more dubious ways that it’s marketed to women. In retrospect, I can’t believe that I haven’t done so yet. The impetus that finally prodded me to get off my posterior and take this on came from what at the time was an unexpected place but in retrospect shouldn’t have been. You’ve met her before quite recently when SBM partner in crime Peter Lipson took her apart for parroting anti-vaccine views and even citing as one of her sources anti-vaccine activist Sherri Tenpenny. I’m referring, unfortunately, to one of Oprah Winfrey’s stable of dubious doctors, Dr. Christiane Northrup. Sadly, Peter’s example of her promotion of vaccine pseudoscience is not the first time we at SBM have caught Dr. Northrup espousing anti-vaccine views. We’ve also harshly criticized her for her promotion of “bioidentical hormones” and various dubious thyroid treatments. However, Dr. Northrup is perhaps most (in)famous for her advocating on Oprah’s show the use of Qi Gong to direct qi to the vagina, there apparently to cure all manner of female ills and promote fantastic orgasms in the process. This little incident ought to tell you nearly all that you need to know about her. Even Oprah looked rather embarrassed in the video in which Dr. Northrup led her audience in directing all that qi goodness “down below.”

What brought Dr. Northrup to my attention again was my having joined her e-mail list. As you might imagine, I’m on a lot of e-mail lists, ranging from that of Mike Adams, to Generation Rescue, to Joe Mercola and beyond. I do it all for you, in order to have the blogging material come to me rather than my having to seek it out. True, the price is that my e-mail in box is frequently clogged with quackery, but it’s a small price to pay. This time around, Dr. Northrup’s e-mail brought my attention to a post of hers, Best Breast Test: The Promise of Thermography. It was truly painful to read, and I consider it inexcusable that someone who claims to be an advocate of “women’s health” could write something that reveals such ignorance. But, then, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised after her recent flirtation with anti-vaccine views. If it isn’t already complete, Dr. Northrup’s journey to the Dark Side is damned close to complete. You’ll see what I mean right from her very introduction:

Every year when Breast Cancer Awareness Month (October) comes around I am saddened and surprised that thermography hasn’t become more popular. Part of this is my mindset. I’d rather focus on breast health and ways to prevent breast cancer at the cellular level than put the emphasis on testing and retesting until you finally do find something to poke, prod, cut out, or radiate.

Let me take a moment to note the framing that Northrup uses. She’s all about “prevention,” or, at least, that’s what she wants you to think she’s all about. This is no doubt meant to be a stark contrast to us reductionistic, “Western,” “allopathic” physicians who, according to typical “alt-med” tropes, don’t give a rodent’s posterior about prevention but only care about, as Northrup so quaintly put it, “poking,” “prodding,” “cutting out,” and “irradiating.” The only alt-med trope Northrup left out of her attempt to don the mantle of prevention is “poisoning.” (I suppose I should be thankful that she managed to restrain herself that much.) But what does it mean to “prevent breast cancer at the cellular level”? That’s just a scientifically empty and meaningless buzz phrase, especially coming from her.

How would thermography achieve “prevention at the cellular level”, anyway? Thermography is just another test. In intent the use of thermography is no different than mammography in that its advocates claim that thermography can find breast cancers at an early stage. Its advocates also use thermography in damned close to exactly the same way that we use mammography. They use the test on asymptomatic women periodically to try to detect cancer early. There’s zero “prevention” involved. Even if thermography worked as well as its proponents (like Dr. Northrup) claim, there would still be zero prevention involved. Northrup’s use of the term “prevent breast cancer at the cellular level” is as empty as her head is apparently of knowledge about breast cancer and as empty as her handwaving about thermography.

Yes, it’s utter nonsense, but Dr. Northrup’s blather does echo many of the claims made for thermography. For instance, if you go to BreastThermography.com, a site that is clearly pro-thermography, you’ll find a whole bunch of similar claims, such as that thermography detects cancer earlier, that it can provide an “individualized breast cancer risk assessment,” that it’s better for younger women, and that it can detect “thermal signs of hormone effects” that can be used for breast cancer prevention. It ends up including the groundless recommendation that “every woman should include breast thermography as part of her regular breast heath care.” Pointing out that the “incidence of breast cancer is on the rise” (it isn’t, by the way, and hasn’t been for years; in fact, it’s decreasing), the website then makes the completely baseless recommendations that every woman should have a baseline scan at age 20 and then be scanned every three years between ages 20-30 and every year after age 30.

BreastThermography.com also has a quack Miranda warning on its front page:

Disclaimer: Breast thermography offers women information that no other procedure can provide. However, breast thermography is not a replacement for or alternative to mammography or any other form of breast imaging. Breast thermography is meant to be used in addition to mammography and other tests or procedures. Breast thermography and mammography are complementary procedures, one test does not replace the other. All thermography reports are meant to identify thermal emissions that suggest potential risk markers only and do not in any way suggest diagnosis and/or treatment. Studies show that the earliest detection is realized when multiple tests are used together. This multimodal approach includes breast self-examinations, physical breast exams by a doctor, mammography, ultrasound, MRI, thermography, and other tests that may be ordered by your doctor.

All of which would be fine as far as it goes, except that thermography shouldn’t be considered anything more than an experimental technique and the above paragraph does not describe how Northrup is promoting thermography.

Thermography: The Data

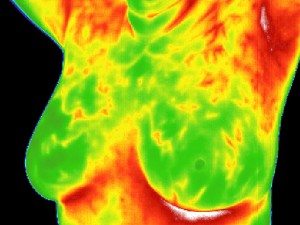

What is thermography and how is it used to detect breast cancer? As its name implies, thermography measures differences in temperature. Most systems use infrared imaging to achieve these measurements. There’s nothing magical about it; the technology has been in use for various applications for decades. The rationale for applying thermography to the detection of breast cancer is that breast cancers tend to induce angiogenesis, which is nothing more than the ingrowth of new blood vessels into the tumor to supply its nutrient and oxygen needs. A tumor that can’t induce angiogenesis can’t grow beyond the diffusion limit in aqueous solution, which is less than 1 mm in diameter. These blood vessels result in additional blood flow, which results in additional heat. In addition, the metabolism of breast cancer cells tends to be faster than the surrounding tissue, and cancer is often associated with inflammation, two more reasons why the temperature of breast cancers might be higher than the surrounding normal breast tissue and therefore potentially imageable using infrared thermography.

Although thermography is scientifically plausible, unfortunately its reality has not lived up to its promise, Dr. Northrup’s claims notwithstanding. Let’s take a look at those claims:

I understand that mammography has been the gold standard for years. Doctors are the most familiar with this test, and many believe that a mammogram is the best test for detecting breast cancer early. But it’s not. Studies show that a thermogram identifies precancerous or cancerous cells earlier, produces unambiguous results (which cuts down on additional testing), and doesn’t hurt the body.

No, studies do not show anything of the sort, other than that thermography probably doesn’t hurt the body. In particular thermography does not produce unambiguous results—far from it! That’s the problem, and that’s the reason why thermography has not caught on. It’s unreliable, and it doesn’t provide much in the way of anatomic information that allows a better localization of the breast cancers it does find. You’ll note if you look at Dr. Northrup’s article that the most recent article she cites that directly addresses the use of thermography to detect breast cancer is from 1982. There are more recent reviews and studies, as you might expect, but, oddly enough, Dr. Northrup doesn’t cite them.

One aspect of thermography for breast cancer detection that its advocates almost always mention is that it is FDA-approved for the detection of breast cancer. That is true, but not in the way it is often implied. Yes, thermography is FDA-approved for the detection of breast cancer, but what they don’t tell you is that thermography is not approved alone for screening women for the detection of breast cancer. It’s approved to be used in conjunction with mammography. What thermography boosters also fail to tell you is that the reason why thermography fell out of favor 30 years ago was as a result of a study by Feig et al in 1977 that found thermograpy to come in dead last among existing screening modalities of the time in finding breast cancers. Mammography detected 78% of breast cancers. In contrast, thermography only detected 39%, and in all 16,000 women in the study thermography was interpreted as positive in 17.9%. This is not a stellar record. In a separate trial in the early 1970s, the Breast Cancer Detection Demonstration Project (BCDDP) planned to compare thermography, mammography and clinical examination. However, BCDDP investigators decided to drop thermography early in the project due to a high false positive rate and low sensitivity.

Of course, technology was a lot more primitive back then, both in its ability to detect differences in temperature and its ability to produce images; it’s not at all surprising that thermography would not perform as well. Add to that the problems of bulky equipment, some of which required liquid nitrogen to work, and the lack of computational power to analyze images, and it’s not surprising that, compared to mammography, thermography never really caught on. Indeed, in a 1985 review, Moskowitz analyzed the data from the BCDDP trial. Of the 1,260 patients with more than one positive thermogram from 1973 to 1976, 1.9% subsequently developed breast cancer from 1977 to 1983. That finding was not statistically significantly different from the 1.3% of patients who developed cancer and never had a positive thermogram. His review of the literature supported the dismal record of thermography for detecting breast cancer.

That was 30 years ago, though. What about now? Computing power has increased almost ridiculously since then, and newer thermal sensors can detect temperature differences of 0.08° C. Has technology evolved to the point where the shortcomings of the original studies that buried thermography as a viable competitor to mammography for breast cancer screening no longer apply?

Maybe. Maybe not. That’s exactly the problem. As pointed out by Gregory Plotnikoff, M.D., M.T.S., and Carolyn Torkelson, M.D., M.S. in a 2009 commentary in Minnesota Medicine entitled Emerging Controversies in Breast Imaging: Is There a Place for Thermography?:

The biggest question concerns the efficacy of thermography to detect breast cancer. Despite various studies that suggest positive results for thermography, there has never been a major randomized controlled trial to determine baseline measurements of sensitivity and specificity. It is hard to imagine thermography being accepted by the conventional medical establishment without such data or evidence of cost-effectiveness.17 In addition to questions about the effectiveness of thermography, research needs to be conducted to determine the cost of using it for widespread cancer screening.18

Even two naturopaths reviewing the thermography literature in 2009 in one of the most woo-friendly journals imaginable, Integrative Cancer Therapies, conclude:

In light of developments in computer technology, and the maturation of the thermographic industry, additional research is required to confirm and/or continue to develop the potential of this technology to provide effective noninvasive early detection of breast cancer.

Even though the naturopaths tried very hard to spin the data into as favorable a view as possible, they just couldn’t bring themselves to recommend routine thermography. Meanwhile, virtually every reputable professional organization whose purview includes breast imaging and breast cancer does not recommend it. Here is a typical position statement, this time from cancer organizations in New Zealand.

That’s not to say that there aren’t “positive” trials of thermography. The problem is that they don’t rise to the level necessary to justify recommending thermography to all women, as many of these chiropractors and naturopaths are doing. There was a recent study of 92 women in 2008 that, using a technology called Digital infrared thermal imaging (DITI), found a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity ranging between 12-44%, depending upon the setting of the machine. While this is promising, it’s not possible to justify the widespread use of this technology on the basis of such a small clinical trial. One also has to remember that thermography also has downsides relative to mammography. For example, women have to let their skin temperature equilibrate to the room temperature of the thermography suite by sitting naked from the waist up in the dressing room for 15 minutes before the examination can be done:

For the scan, the patient is asked to stand about 10 feet in front of the camera with her arms raised over her head while three views of the breast (anterior and two lateral views) are taken. The next step in the process is a “cold challenge” where the patient is asked to place both hands in cold water at 10°C for one minute; then these same three images are retaken.43,44 The breasts exhibit thermal patterns that are captured by the infrared camera. It is these thermal captured image patterns that are interpreted by a trained thermographer.

Other protocols I’ve read about include blowing cool air on the breasts to speed the equilibration.

There is also considerable opportunity for subjectivity in the interpretation of thermograms. This is because, in marked contrast to mammography, there aren’t any widely agreed-upon standards for the performance and interpretation of breast thermography. Plotnikoff and Torkelson described the state of the industry quite well, with one huge blind spot:

In its current state in the United States, thermography is a balkanized industry. Although thermography never took root in mainstream medicine, it has begun to flourish in alternative settings as a breast cancer detection service offered by some physicians, chiropractors, and naturopaths. In lieu of any industry or professional standards for thermography, a variety of practices and protocols have emerged among practitioners and equipment manufacturers. As one practitioner described it, the industry is in its “Wild West” days.19 This fragmented state weakens the credibility of the entire field because consumers have no way to distinguish credible from inferior thermographic techniques. As thermography emerges as an alternative screening tool, consumers are led to believe that it has been validated for efficacy and compared with mammography. This misconception could raise public-safety concerns.

“Misconception”? Have Plotnikoff and Torkelson been reading the ads for breast thermography on the web? These go far beyond simply claiming that thermography has been validated for efficacy and compared with mammography.

The marketing of thermography by CAM practitioners

Thermography has become very popular among chiropractors, homeopaths, naturopaths, and a wide variety of “alternative practitioners.” Indeed, many are the ads that claim that thermography is safer than mammography and that it can replace mammography for breast cancer screening, particularly for younger women. Typical of such marketing and propaganda is this article by Joe Mercola entitled Revolutionary and Safe Diagnostic Tool Detects Hidden Inflammation: Thermography as a means of marketing the test at Dr. Mercola’s Natural Health Center in the Chicago area:

In this ad, Mercola claims that mammograms cause breast cancer, that the compression used during mammography can lead to “a lethal spread of any existing malignant cells,” and that thermograpy can identify inflammation that leads to cancer that can be treated—all using diet and Mercola’s supplements, of course—to prevent breast cancer. He also claims that thermography is good for more than just breast cancer detection. If you believe Mercola, it can also detect a whole panoply of conditions, including arthritis, immune dysfunction, fibromyalgia, carpal tunnel syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, and Crohn’s disease.

Geez, is there anything thermography can’t do?

Well, if we’re to believe Dr. Northrup, this is another thing breast thermography can do:

The most promising aspect of thermography is its ability to spot anomalies years before mammography. Using the same ten-year study data,2 researcher Dr. Getson adds, “Since thermal imaging detects changes at the cellular level, studies suggest that this test can detect activity eight to ten years before any other test. This makes it unique in that it affords us the opportunity to view changes before the actual formation of the tumor. Studies have shown that by the time a tumor has grown to sufficient size to be detectable by physical examination or mammography, it has in fact been growing for about seven years achieving more than twenty-five doublings of the malignant cell colony. At 90 days there are two cells, at one year there are16 cells, and at five years there are 1,048,576 cells—an amount that is still undetectable by a mammogram. (At 8 years, there are almost 4 billion cells.)”

Of course, even if this were true (and no evidence is presented to show that it is), as I’ve pointed out time and time again, ever earlier detection of cancer is not always a good thing because not all early lesions progress to become cancer. In other words, detecting breast cancer earlier is in general a good thing most of the time, but there clearly exists a point of diminishing returns and a point beyond which detection that is too early has the potential to cause harm. The very issue in the recent rethinking of recommendations for mammography (most recently discussed just two weeks ago) hasn’t been that mammography is not sensitive enough, but rather its potential to detect too many breast cancers that would never progress to endanger the life of the woman.

Let’s put it this way. Even if everything Northrup says or cites is absolutely accurate and thermography can detect inflammatory states that lead to cancer several years before mammography, that would not necessarily save even a single life but would have the potential to cause even more harm through overdiagnosis and overtreatment, particularly given that as many as one in five mammographically detected breast cancers might never progress—and some might even regress. Detecting such lesions five to ten years earlier could only exacerbate the problem of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. It might also lead to the perfect situation for CAM practitioners. They could find breast “lesions” with thermography; prescribe “treatments” in the form of dietary manipulations, supplements, or whatever; watch the lesions either disappear spontaneously or not progress; and then claim credit for having “cured” or “stopped the progression of” the cancer. Even if the cancer progresses to where it requires surgical removal and other treatment, the quack can claim credit for having detected it “before mammography.”

If you want evidence that Dr. Northrup has truly gone completely woo, look no further than this next passage:

As with anything, I suggest you let your inner guidance help you in all decisions about your health. If you feel it’s best to get an annual mammogram, then by all means continue with them. Just be aware of the drawbacks and risks associated with the test. One helpful way to assess your risk for breast cancer—which in turn can help you decide how often you want to have mammograms—is to use the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, available online at www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool. After you answer seven simple questions, it calculates both your risk of getting invasive breast cancer in the next five years as well as your lifetime risk, and it compares each to the risk for the average U.S. woman of the same age and race or ethnicity.

You would be surprised by how many women tell me their doctors make them feel guilty for not having a mammogram. Women who just know they have healthy breasts. Don’t be intimidated if you prefer to forgo annual mammography.

If Dr. Northrup truly tells her patients that it’s medically acceptable for them to forego mammograms and use thermography instead for their routine screening for breast cancer, she is guilty of gross malpractice, in my opinion. If she doesn’t tell her patients that but writes articles like the one I’m citing, she’s guilty of hypocrisy. Her statements are scientifically unjustified, profoundly unethical, and potentially dangerous to patients. Many are the women whom I’ve met who “just knew” they were fine until their family persuaded them to undergo mammography, which then found real, invasive cancers. I don’t have much faith in anyone’s “inner guidance” with regard to asymptomatic disease. In essence, Northrup is urging women to base their health care decisions on intuition rather than science.

The bottom line

Thermography is a technology that has some degree of scientific plausibility but has not been validated as a diagnostic modality to detect breast cancer. The studies from 30 years ago showed it to be markedly inferior to mammography for this purpose, the claims of naturopaths, chiropractors, and various other quacks notwithstanding. While it’s true that advances in technology and computing power might have brought thermography to a point where it might be a useful adjunct to current imaging techniques, large randomized clinical trials have not been done to define its sensitivity and specificity and determine its utility when added to routine mammographic screening. In addition, thermography doesn’t provide any information that breast MRI can’t provide—and provide better. MRI measures in essence the same thing that thermography does (blood flow, which is what the heat maps that thermography produces are surrogates for) and adds to it detailed anatomic information that can guide biopsy and excision. That’s something thermography can’t do.

Currently, my take is that thermography might be useful as an adjunct to mammography. Indeed, I’ll make a confession. Back when I worked at The Cancer Institute of New Jersey, I became involved with a project that was testing a thermography-like machine. (I can’t say more than that about it.) A startup company was testing its new device to determine if the combination of mammography plus this technique could improve the sensitivity and specificity of breast cancer detection. I don’t know what ever became of the company or the device, but I still view thermography basically the same way now as I did then. It’s a test that might be useful as an adjunct to mammographic screening. In order to determine whether thermography is useful as an adjunct to other imaging techniques, however, its proponents need to do the proper scientific validation and clinical testing first, which haven’t been done yet and will require large clinical trials. Until that testing is done, thermography should not be offered to women outside of a clinical trial, and it should never be offered to women in lieu of mammography to detect breast cancer. Science does not support the former indication, although I have to concede that it might one day. More importantly, science most definitely does not support the use of thermography instead of mammography, a use that I doubt any clinical trial is likely ever to support because clinical equipoise demands that thermography be added to mammography in any clinical trial, not tested instead of mammography.

The ironic and sad thing about thermography is that it is not per se quackery itself. The concept of breast thermography is based on a reasonable and scientifically plausible idea, namely that tumors produce more angiogenesis, which leads to more blood flow, which leads to more heat that can be detected and imaged. However, the way it is marketed and promoted as a replacement for mammography is quackery, and Dr. Northrup is buying into such highly dubious promotion, coupled with a condescending appeal to “women’s intuition.” Unfortunately, the tight embrace of quacks to thermography contributes to the unsavory reputation the technique currently has in the medical community and continues to hinder its development in mainstream scientific medicine. On the other hand, maybe the quacks like it that way. If mainstream medicine were ever to validate thermography scientifically, then it would become science-based medicine, and the quacks can’t have that. It’s too profitable to market the test through fear and misinformation.